What makes Oshogatsu, the Japanese New Year, so special? Celebrated from January 1-7, Oshogatsu is not just a holiday but a deep cultural tradition in Japan. It’s a time of unique traditions and foods, offering a glimpse into Japan’s rich culture and heritage, distinct from Lunar New Year celebrations in other Asian countries.

The Historical Significance of Oshogatsu

The Roots of Oshogatsu

Oshogatsu, the Japanese New Year, has its origins in ancient agricultural practices, marking one of Japan’s oldest festivals centered on welcoming the deities for a bountiful harvest. This celebration deeply influenced by Japan’s agrarian past, was essential for a good harvest in a predominantly farming society. As centuries passed, Oshogatsu evolved, integrating Buddhist traditions introduced in the 6th century with native Shinto rituals. This blend of religious practices, alongside the shift to the Gregorian calendar in 1873, has shaped the modern Oshogatsu while preserving its historical significance and cultural richness.

Toshigami-sama and Oshogatsu Traditions

At the heart of Oshogatsu celebrations is Toshigami-sama, a deity believed to bring prosperity, fertility, and happiness in the coming year. Japanese customs during Oshogatsu are designed to honor and welcome Toshigami-sama into homes, involving thorough house cleaning and the preparation of special offerings. The celebration also once featured the “counted year” system, where all Japanese would symbolically age a year on New Year’s Day, highlighting the communal spirit of the occasion. Despite changes over time, these traditions underscore the enduring cultural and spiritual essence of Oshogatsu.

Regional Variations and Contemporary Observances

Oshogatsu is celebrated throughout Japan, yet regional differences highlight the country’s diverse cultural landscape. For instance, Okinawa and other southwestern islands might observe the Lunar New Year, incorporating unique rituals and festivities. Today, while the agricultural and religious underpinnings of Oshogatsu may have faded, its cultural importance endures. Modern celebrations focus on family gatherings, shrine visits for Hatsumode, and participation in traditional games, maintaining Oshogatsu’s role as a pivotal time of reflection, renewal, and joy in Japanese society.

Oshogatsu Cuisine

Oshogatsu, the Japanese New Year, is as much a feast for the palate as it is a celebration of renewal and culture. The cuisine served during this festive period is not just about savoring delicious dishes but also about honoring traditions and welcoming good fortune.

Ozoni: A Symbolic Soup

Ozoni, a traditional soup enjoyed during Japan’s Oshogatsu (New Year), showcases the country’s regional culinary diversity. Its base varies from a clear soy sauce broth in Eastern Japan to a white miso soup in the West, reflecting local preferences and traditions. Ingredients like mochi (rice cake), symbolizing longevity and family unity, and chicken, representing prosperity, add rich layers of meaning. The varied shapes and components of Ozoni across regions highlight Japan’s deep cultural tapestry and the symbolism infused in New Year celebrations.

Osechi-Ryori: The Art of Layered Flavors

Osechi-ryori is a collection of traditional Japanese New Year foods packed in Jubako, which are special lacquered boxes. These foods are not only delicious but are also laden with symbolism. Each layer of the Jubako and each dish within it represents different wishes for the New Year.

Key Dishes and Their Meanings

- Kuromame (Sweet Black Beans)

Symbolizes health and hard work. The word ‘mame’ also means health and diligence in Japanese. - Kazunoko (Herring Roe)

Represents fertility and wishes for a prosperous family. - Tazukuri (Candied Sardines)

Symbolizes an abundant harvest, as sardines were historically used as fertilizer in rice fields. - Kobumaki (Kelp Rolls)

Kelp symbolizes joy and happiness, and the word ‘kobu’ is a homonym for ‘yorokobu,’ which means to be happy in Japanese. - Kamaboko (Fish Cake)

Typically presented in red and white, representing celebratory colors in Japan. Red kamaboko is believed to ward off evil spirits, while white symbolizes purity. - Datemaki (Sweet Rolled Omelette)

Symbolizes knowledge and learning. It is especially popular among students and scholars for its wishful meaning. - Namasu (Vinegared Daikon and Carrot)

A dish made of thinly sliced daikon and carrot marinated in vinegar. Red and white are auspicious colors in Japan, and the dish represents a refreshing start to the New Year. - Ebi (Prawns)

Represents longevity, as the bent back of the prawn resembles an elderly person. It is a wish for a long life. - Tai (Sea Bream)

A play on words, as ‘tai’ is part of the word ‘medetai,’ meaning auspicious or celebratory in Japanese. - Ikura (Salmon Roe)

Symbolizes prosperity and fertility. - Gomame (also known as Tazukuri)

Small dried sardines cooked in soy sauce. They symbolize a wish for a good harvest as they were used as fertilizer in olden times. - Chikuzenni (Braised Chicken and Vegetables)

A hearty dish made with chicken, root vegetables, and konnyaku (jelly-like food made from konjac yam), symbolizing a bountiful harvest. - Kinpira Gobo (Braised Burdock Root)

Represents strength and stability, as gobo (burdock root) grows deep into the ground.

Other Traditional Dishes:

- Soba (Buckwheat Noodles)

Eating toshikoshi soba on New Year’s Eve is a tradition that symbolizes letting go of the hardships of the past year and wishing for a long and healthy life. - Zoni Varieties

While Ozoni is a soup with mochi, Zoni is another version, often sweeter and can include ingredients like red beans, further highlighting the regional culinary diversity of Japan. - Sweet Treats

Traditional Japanese sweets, such as “Kagami mochi” and “Kohaku mochi” (red and white rice cakes), are also important, representing purity and the spiritual world.

Customs and Decorations

The customs and decorations of Oshogatsu, the Japanese New Year, are deeply symbolic and reflect the country’s rich cultural heritage. These traditions are not merely ornamental but are imbued with meanings and intentions, playing a crucial role in welcoming the New Year and bidding farewell to the old.

Kadomatsu: The Pine and Bamboo Decoration

The kadomatsu, an essential Oshogatsu decoration, symbolizes longevity, prosperity, and steadfastness through its composition of pine and bamboo. Pine embodies endurance and youth, while bamboo signifies prosperity with its rapid growth. Traditionally arranged in pairs with three bamboo shoots of varying lengths and pine branches, kadomatsu are placed at entrances to welcome ancestral spirits and Toshigami-sama, the New Year deity. This practice not only adorns homes and businesses but also connects Japan’s cultural heritage with the hopeful spirit of the New Year.

Shimekazari: The Sacred Straw Festoon

The Shimekazari, a sacred Shinto decoration for Oshogatsu, combines elements of protection and welcome. Made from shimenawa (sacred straw rope), it’s adorned with symbols of abundance and purity, such as oranges and white paper strips (shide), and hung on doors to create a purified space for Toshigami-sama, the New Year deity. This act signifies warding off evil while inviting prosperity, symbolizing a fresh start and the sanctity of the home as a place for blessing and renewal in the Japanese New Year.

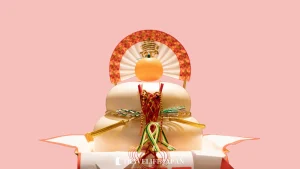

Kagamimochi: The Mirror Rice Cake

Kagamimochi is a ceremonial Japanese New Year offering, consisting of two round rice cakes and a daidai orange, symbolizing continuity, self-reflection, and purity. This tradition, rooted in Shinto beliefs, involves displaying the kagamimochi to honor deities, followed by the “Kagami Biraki” ceremony on January 11th, where the mochi is broken and eaten, symbolically sharing the deity’s blessings with the family. This practice embodies the spirit of renewal and gratitude, central to Japan’s Oshogatsu celebrations, and fosters a sense of communal well-being and spiritual refreshment.

Ema: Wooden Wishing Plaques

Ema are wooden plaques at shrines where visitors inscribe New Year wishes, a unique Japanese custom. Hung at the shrine, these plaques serve as a medium for wishes to reach deities, embodying the hope that these desires will be fulfilled. This practice is a heartfelt part of Japan’s New Year traditions.

Engimono: Lucky Charms and Decorations

Engimono encompasses a range of charms like the Daruma doll and Maneki Neko, each symbolizing good luck and fortune in Japan. Daruma represents resilience, while Maneki Neko invites wealth, commonly placed in businesses. These traditional tokens reflect cultural beliefs in luck and the pursuit of prosperity and success.

Conclusion

Oshogatsu in Japan is a blend of deep-rooted traditions, delectable foods, and meaningful customs, offering a unique experience distinct from other New Year celebrations. Whether you’re decorating with traditional ornaments, savoring Osechi-ryori, or participating in “Hatsumode” (the first shrine visit of the year), embracing these customs can provide a deeper understanding and appreciation of Japanese culture. Oshogatsu is not only a celebration but a testament to Japan’s rich heritage, bridging the past with the present.

CONTACT US

For studying Japanese in Japan, please contact us.